I love birds. Whenever I’m walking outside and hear birdsong, I cock my ear to listen. It’s been a few years since I started paying attention to their voices, and little by little I’ve learned to tell species apart by sound—and in doing so, to feel the passing of the seasons.

I’m fond of the voices of small creatures. The owner of an enchanting chirp is hard to spot. A crow’s call isn’t all that appealing and the bird itself is easy to find, but a nightingale that sings beautifully is much harder to pin down.

Other animals whose calls I enjoy are frogs and crickets, and they, too, are difficult to locate.

Since ancient times, instruments that imitate these animal sounds have existed—what we now call folk instruments. Long before instruments could change pitch precisely or play harmonies, such tools were used to communicate with animals or to express a bond with them in rituals and festivals.

Why do the animals whose sounds I love make those sounds? The Japanese researcher Toshitaka Suzuki discovered linguistic structure in the calls of the Japanese tit: they carry on conversations with grammar. Frog choruses are thought to mark territory, yet in field recordings of Australian frogs captured by the artist Felix Hess, two frogs can be heard skillfully adjusting their timing so their calls don’t overlap—fascinating to hear. For them it may be a territorial display, but to me it sounds like experimental music generating intricate rhythms.

It’s only natural that animals respond to recordings of their own calls, provided the frequencies fall within their hearing range; playback is routine in ethology. But do they ever react to the sounds of instruments that only resemble their calls to human ears?

At the very least, an AI birdsong detector didn’t respond to the sound of a bird-call whistle. I wonder if animals in the mountains would react somehow. What is at the heart of their acoustic communication—frequency, timing? Within the same species? Between different species? Does the predator–prey relationship change things?

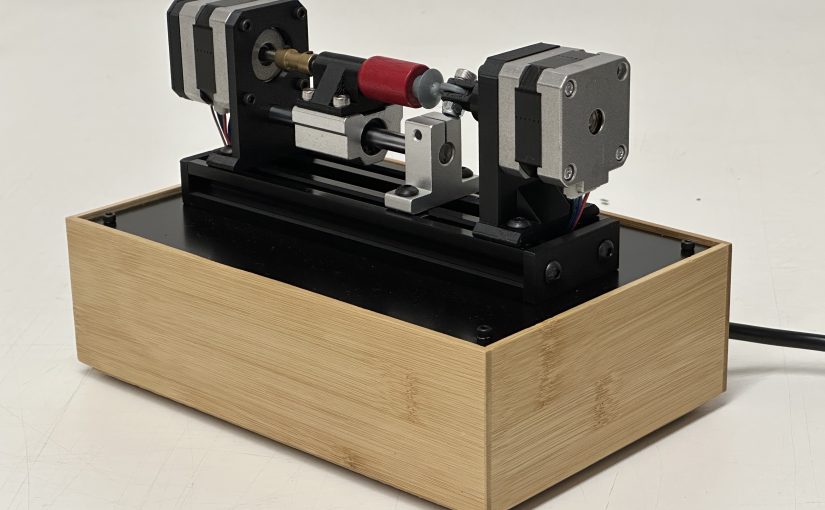

I’m neither a bird nor a frog, so I can’t know what mood they’re in or what meaning their sounds carry. Yet as I imagine it, I design sound-making robots and devise algorithms. The robots are programmed to produce sounds in a way that, in my own way, lets them “become” those animals.

Text and photo: So Kanno